Do We Want To Perform Or To Learn? Is There A Difference?

This post intends to provide guidance for parents as to what to expect and pursue in the developmental stages of their children throughout youth soccer.

Empathy is one of Rush Soccer’s core values, and we believe it requires little empathy to understand parents’ love for their children and their desire to stay involved. That doesn’t mean, with all due respect, that parents know exactly how to be involved and what they should expect from their children’s experience along youth soccer.

Many times, we take winning as a measuring stick. If the team wins, it means we are doing something right, correct? No, it actually does not mean we are doing anything right. Soccer is the only sport in which you can do everything wrong and still win. Competing to win is a different story. Competing to win is not only desirable, but natural, everybody competes with the desire to win, but winning itself can be a misleading parameter when we talk about youth soccer. Let me explain why.

The first thing that we need to cover is that the objective of youth sports is not to win but to develop better players and better people. Like Ruben Rossi, one of the most renowned youth soccer developers in the world told us a few weeks ago:

In youth soccer, winning is never an objective, it is a reward – Ruben Rossi

The reason behind this statement relies on understanding the difference between Performance and Learning. Quoting Nick Soderstrom (Ph.D. in cognitive psychology):

Learning refers to relatively permanent changes in knowledge or behavior. It is — or at least should be — the goal of education. Performance, on the other hand, refers to temporary fluctuations in knowledge or behavior that can be measured or observed during (or shortly after) instruction. – Nick Soderstrom

Or using a passage from an interview we conducted with John O’Sullivan:

“You cannot recognize learning in the moment. This is performance. Learning is being able to retrieve the information and skill over time. Learning happens over time. Many parents (and coaches) confuse performance for learning”. – John O’Sullivan

Let me translate this onto a (pretty bad) example that you’ll easily relate to. If I told (as a coach) your son/daughter ‘Johnny/Susie, when you get the ball off of a throw in, turn and play a long switch to the other side’, they will surely do it and maybe it would even be effective for the team, but has any learning taken place?

Imagine now that instead of saying that, I would have referred to the situation as follows: ‘Johnny/Susie, as we play I want you to think about attacking throw ins, what do you notice about the playing space? Don’t tell me now, let’s chat about it at the end of this activity’. Now Johnnie or Susie will return 30 minutes later, after an extensive thought process, possibly with an answer of the type ‘Coach, the space gets crowded, there’s not a lot of space to play’, to which I could continue to guide by saying ‘That’s correct. Now.. we know that the field is always the same size, so if it’s crowded in one area, what’s that telling you about the others?’.

As you can see, now Johnnie or Susie are reaching the conclusion that switching sides immediately can be a solution during offensive throw ins, but the process was a lot slower, yet there’s learning taking place, they’re building their game understanding, what will generate not only transference to other game situations, but also, as John O’Sullivan mentioned, they will be able to retrieve the information in the future.

That’s why the main objective of a youth club is to develop players, not to win, because the focus should be to help players learn.

Here, in fact, is a video from Dr. Bjork (who Nick S. will cite later on) explaining this process.

Always keep the eye in the long term vision. I’d sacrifice all the gold medals at U9 and U10 if I knew we are doing everything to see my child’s top potential at U19.

Moreover, I’ll give you a tip: Worry if your children are winning too much, because if they are, that probably means they’re not being challenged at the level they should be, and that limits their development.

That’s why at Rush Soccer we have a policy that we call ‘6-3-1’, that is a desired record for a team along a season: 6 wins, 3 loses, 1 tie. We use it as a measuring stick to set an appropriate level of challenge for the players to be exposed to.

Hang on… Are you telling me that you want them to fail, to lose? Yes, we are.

I’ll wrap it up with one more passage from Nick Soderstrom, look how interesting this is:

There’s no doubt that performance gains can fail to support learning gains. As my initial example illustrated, progress during a lesson can be misleading in terms of what has been retained and can fool teachers and students alike. This is especially true if the performance gains are achieved by using teaching strategies that are designed to produce rapid progress. For example, doing the same type of problem repeatedly in class can lead to rapid, yet fleeting, gains in short-term performance.

But what about the flip side? If increased performance can lead to decreased learning, can decreased performance lead to increased learning? The answer is ‘yes.’ As counterintuitive as it sounds, long-term learning can be enhanced by intentionally impairing short-term performance.

The learning strategies that fall under this category are called desirable difficulties (Bjork, 1994). They are desirable because they lead to better long-term retention and transfer of knowledge, and they are difficult because they pose challenges that slow the rate of current progress and induce more mistakes during instruction or training.

In a nutshell, the concept of desirable difficulties embodies the adage: no pain, no gain. Just like how taking the stairs is better for our health than taking the escalator, making learning more challenging can lead to better retention.

This sounds simple but has profound implications in the way clubs and coaches approach the work, and I think this is very important because you as a parent should demand this from your club.

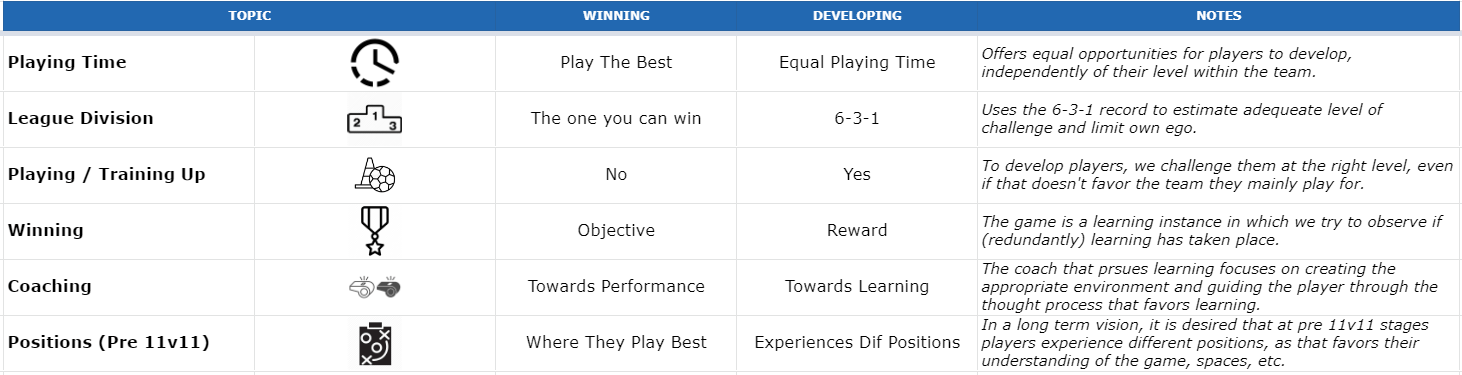

I’ve had this conversation with parents several times, so trying to find good examples I came up with what I call the ‘winning vs developing chart’ (said as an equivalent of performance vs learning approach). This chart offers concrete, visual differences between coaching for learning versus coaching for development.

I’m sharing it with you because, once again, I actually hope you hold your club and coach accountable for this. Check below.